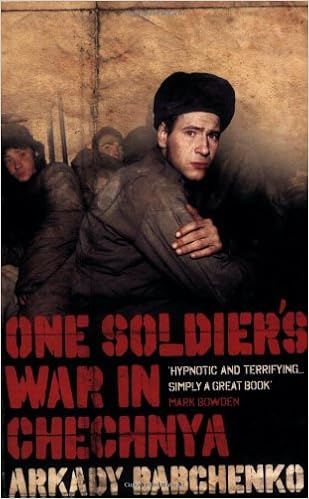

One Soldiers War in Chechnya

Language: English

Pages: 304

ISBN: 1846270405

Format: PDF / Kindle (mobi) / ePub

Arkady Babchenko didn't write about fighting in Chechnya to make his name as an author, nor to mount a political attack against Russia's rulers. He wrote to recover.

"Writing was the only thing that helped," he says of the months following his demob. "If I hadn't started writing, I might have lost myself to drink. It was the only real cure.

What poured out of him is an unflinchingly un-macho record. No comforting heroes or villains; no familiar arc of near-defeat and triumph-against-the-odds. Instead Babchenko presents us with a relentless account of fear, boredom, confusion, filth, cold, disease, hunger, thirst and lingering dread.

These notes became One Soldier's War in Chechnya, his memoir of the Chechen conflict.

The Russian army is a dangerous place, even in peace, even miles from the enemy. One Soldier's War is probably at its most disturbing - and most powerful - when Babchenko describes the younger soldiers cowering in fear of the older men. Drunk, seemingly deranged bullies drag them out of bed, half-kill them, threaten to rape them and then beat them all over again for daring to have black eyes.

But almost as shocking is the inability of Russia to provide even the basics for its soldiers. Babchenko describes soldiers grazing on berries "like moose" or drinking water tainted with rotting human flesh. A soldier, he believes, has the best chance of survival when he no longer cares whether he lives or dies. "If you think 'a year after the war I'll become a writer', then fate will get you - kill you. Fate is a very subtle, a very sensitive system. You need to be as imperceptible as possible. Then maybe it won't touch you."

Berlin 1961: Kennedy, Khrushchev, and the Most Dangerous Place on Earth

Notes on the Cuff and Other Stories

The Stalin Era (Routledge Sources in History)

The Case of Comrade Tulayev (New York Review Books Classics)

sunbathe half-naked. Then again, Pincha always walks around in several layers of clothing and boots and his feet are usually so dirty you could plant potatoes between his toes. Arkasha tells him he should scrape off the dirt from his feet for blacking his boots and just sell his polish. That always amuses us. It’s forty-five minutes before morning parade and no-one knows why we have been fallen in. We stand for a while, guessing what might have happened, then a rumour spreads along the ranks

skywards and the ground is scattered with rags, papers and other debris. Nearby stands a carrier, apparently in one piece but scorched black. On the other side of the bunker stands a tank, also black. A whole platoon must have died here. We are silent. There is no need to say anything. We are all gripped by the same feeling that affects any living creature in the presence of death. We have suddenly become different - Zyuzik, Andy, the commander, all of us - as if our places have been taken by

When the noise dies down, Sanya calls me again. It’s a running dispute between him and Boxer: who’s the boss and which one I will obey, just like a dog. If I climb up on top again, Boxer will give me a thick ear; if I don’t, then Sanya will. I decide that Sanya is better and climb up again next to him. ‘Hey, you got any weed?’ he asks. ‘No,’ I answer. I don’t like this conversation as I realize where it’s heading. ‘How about you go and get some?’ I shake my head. He clambers over and lowers

we got there, there was no-one in the bunker, just a tin of condensed milk in the middle of the road, and underneath it what we call a ‘petal’, a mean little mine that doesn’t kill but only cripples you, tearing off half your foot or your toes. Pincha threw a loop of wire round it, jumped in the ditch and tipped the tin over. After the blast, we scooped the sticky-sweet stuff with our dirty fingers right there at the block post where they killed our boys. It wasn’t sacrilege; they were already

vodka, one by one, to everybody’s glee, repeating each time; ‘So, infantry, who’s for a drink?’ We lit our cigarettes and sat up on the carrier. I took a drag, and spat, wiping my frozen nose. ‘Bloody Chechnya. I’m frozen like a dog. If only it would freeze properly then at least it would be dry... All I’ve got on underneath is long johns and pants. If you wear your underlining you keel over, it’s heavy as anything, really hard work. And I can’t find any trousers anywhere. Vasya offered me some