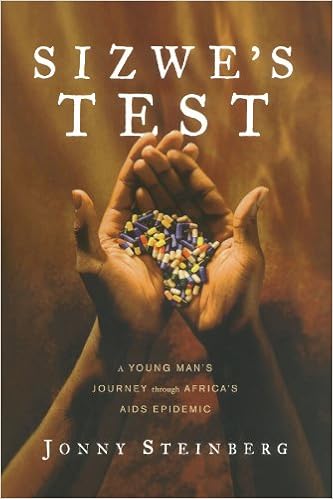

Sizwe's Test: A Young Man's Journey Through Africa's AIDS Epidemic

Jonny Steinberg

Language: English

Pages: 368

ISBN: 1416552707

Format: PDF / Kindle (mobi) / ePub

At the age of twenty-nine, Sizwe Magadla is among the most handsome, well-educated, and richest of the men in his poverty-stricken village. Dr. Hermann Reuter, a son of old South West African stock, wants to show the world that if you provide decent treatment, people will come and get it, no matter their circumstances.

Sizwe and Hermann live at the epicenter of the greatest plague of our times, the African AIDS epidemic. In South Africa alone, nearly 6 million people in a population of 46 million are HIV-positive. Already, Sizwe has watched several neighbors grow ill and die, yet he himself has pushed AIDS to the margins of his life and associates it obliquely with other people's envy, with comeuppance, and with misfortune.

When Hermann Reuter establishes an antiretroviral treatment program in Sizwe's district and Sizwe discovers that close family members have the virus, the antagonism between these two figures from very different worlds -- one afraid that people will turn their backs on medical care, the other fearful of the advent of a world in which respect for traditional ways has been lost and privacy has been obliterated -- mirrors a continent-wide battle against an epidemic that has corrupted souls as much as bodies.

A heartbreaking tale of shame and pride, sex and death, and a continent's battle with its demons, Steinberg's searing account is a tour-de-force of literary journalism.

Global Shadows: Africa in the Neoliberal World Order

African History: A Very Short Introduction (Very Short Introductions)

Women's Roles in Sub-Saharan Africa (Women's Roles through History)

The Lord's Resistance Army: Myth and Reality

Country of My Skull: Guilt, Sorrow, and the Limits of Forgiveness in the New South Africa

You Must Set Forth at Dawn: A Memoir

child is but eight days old, a father does not casually wander into his wife’s parents’ homestead. He waits to be invited. It was an unforgivingly hot late January day. The radio weather report had put the temperature at equal to ninety degrees Fahrenheit. In the car, with the sun pummeling our roof and no trace of a shadow, it was much hotter than that. The homestead was still; not a soul was to be seen. To pass the time, we spoke of Ithanga’s dogs. Sizwe said they were all devoted to him, even

buy with Buyisile’s remittances were soon spent on the people at home. The way Sizwe remembers it, he and his brother were utterly penniless. When they ran out of food, they walked twelve miles home through the forest, picked the vegetables their mother grew in her garden, and walked through the night back to school. It is hard to put together a crisp image of Sizwe during this time. He is an assemblage of paradoxes. Staying in school took monomaniacal determination. The boys may have resented

quiet playfulness. DURING THE FOLLOWING weeks and months, the tale of Hermann’s HIV-laced needles began emerging all over the place, always unsolicited. It was usually a Hermann acolyte who told the story. “Even before Hermann came to our village for the first time, people had heard the rumor that he was bringing AIDS,” a young woman called Doli Mapungu, whom Hermann had hired as a pharmacist assistant, told me. “When he arrived, there was a big crowd outside the clinic. Many were not sick;

rules to define the boundary of one’s club. What is the significance of these particular rules? Those who begin treatment must make a public renunciation. Watched and judged by an audience, they must deny themselves alcohol and nicotine. In Nomvalo, that audience is Kate Marrandi. Closer to the center of the treatment program, it is a support group of peers. In either case, one must submit one’s powers of discipline and restraint to a public test. I took these thoughts to Judge Edwin Cameron,

more troubling and more difficult to manage, but that is another story. THERE IS NO electricity here. The fridge in which Sizwe keeps his beer runs on gas. His hi-fi is in fact an old-fashioned car tape player attached to a large battery. He wants to buy another battery, a much larger one, large enough to run a television set. If he did so, his would be the only television in Ithanga. He would have to build a much larger spaza shop to accommodate his customers, he tells me, because everybody