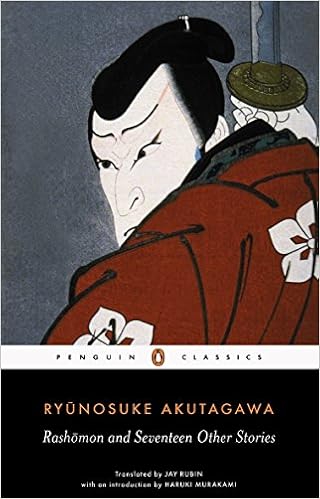

Rashomon and Seventeen Other Stories (Penguin Classics)

Ryunosuke Akutagawa

Language: English

Pages: 268

ISBN: 0140449701

Format: PDF / Kindle (mobi) / ePub

One of Penguin Classics' most popular translations—now also in our elegant black spine dress

Ryünosuke Akutagawa is one of Japan's foremost stylists—a modernist master whose short stories are marked by highly original imagery, cynicism, beauty and wild humour. "Rashömon"and "In a Bamboo Grove" inspired Kurosawa's magnificent film and depict a past in which morality is turned upside down, while tales such as "The Nose," "O-Gin" and "Loyalty" paint a rich and imaginative picture of a medieval Japan peopled by Shoguns and priests, vagrants and peasants. And in later works such as "Death Register," "The Life of a Stupid Man," and "Spinning Gears," Akutagawa drew from his own life to devastating effect, revealing his intense melancholy and terror of madness in exquisitely moving impressionistic stories.

For more than seventy years, Penguin has been the leading publisher of classic literature in the English-speaking world. With more than 1,700 titles, Penguin Classics represents a global bookshelf of the best works throughout history and across genres and disciplines. Readers trust the series to provide authoritative texts enhanced by introductions and notes by distinguished scholars and contemporary authors, as well as up-to-date translations by award-winning translators.

Nagasaki: Life After Nuclear War

The Pillow Book of Sei Shonagon

My Awesome Japan Adventure: A Diary about the Best 4 Months Ever!

Samurai Invasion: Japan's Korean War 1592 -1598

River, known as Mukōjima, was one of Edo’s prime spots for viewing cherry blossoms. 5. elder colleague: The writer Tanizaki Jun’ichirō (1886–1965), best known in the West for such novels as The Key (1956) and The Makioka Sisters (1943–8), attended Tokyo Imperial University from 1908 until he was expelled in 1911 following his widely heralded debut on the literary scene. In 1914 Akutagawa and some friends revived the short-lived literary magazine (see Section 8) that Tanizaki had used to attract

medieval Japanese religious conceptions and provide an ideal introduction to “Hell Screen.” My translation of “The Spider Thread” follows Akutagawa’s manuscript (as in CARZ) rather than the edited version that appeared in the children’s magazine for which it was written (as in IARZ). “Hell Screen,” the story of an artist, can be seen as Akutagawa’s examination of his devotion to his own art, but it works on a more universal level by pitting animal instinct against human intellect and questioning

moment was terrifying in that very way. “In the carriage, a voluptuous noblewoman writhes in agony, her long black hair tossing in the ferocious flames. Her face… well, perhaps she contorts her brows and casts her gaze skyward toward the ceiling of the cabin as she chokes on the rising clouds of smoke. Her hands might tear at the cloth streamers of the carriage blinds as she struggles to ward off the shower of sparks raining down upon her. Around her swarm fierce, carnivorous birds, perhaps a

1868, Akutagawa would undoubtedly be one of them. He might even squeeze in among the top five.1 But what, in the most concrete terms, is a “writer of national stature” in Japan? Such a writer would necessarily have left us works of the first rank that vividly reflect the mentality of the Japanese people of his or her age. This is the most essential point. Of course the works themselves—or at least the writer’s most representative works—must not only be exceptional, they must have the depth and

of Yosaku’s illness and death, however, owing to some error in judgment, she professed an exclusive devotion to the Kirishitan sect and began frequenting the home of one Bateren1 Rodrigue in the neighboring village. Some in this village said that she had become the bateren’s mistress, and she was widely condemned. Her entire family, including her father Sōbē and all her sisters and brothers, tried to reason with her, but she insisted that the most auspicious of all gods was her Deus Come Thus.2