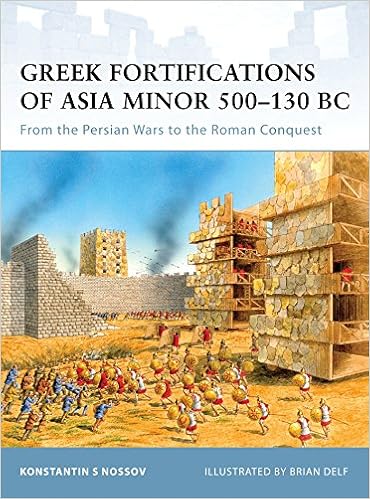

Greek Fortifications of Asia Minor 500-130 BC: From the Persian Wars to the Roman Conquest (Fortress)

Language: English

Pages: 64

ISBN: 1846034159

Format: PDF / Kindle (mobi) / ePub

Sandwiched between the heart of ancient Greece and the lands of Persia, the Greek cities of Western Anatolia were the spark that ignited some of the most iconic conflicts of the ancient world. Fought over repeatedly in the 5th century BC, their conquest by the Persians provided a casus belli for Alexander the Great to cross the Hellespont in 334 BC and launch the battle of Granicus and the sieges of Miletus and Halicarnassus. A blend of Greek and Asian styles of military architecture, these fortified cities were revolutionary in their multi-linear construction - successive defensive walls - with loopholes and mural arches. Konstantin Nossov illustrates the evolution of Greek fortifications and the influences of the region they bordered in this fascinating study.

The Battle of Salamis: The Naval Encounter That Saved Greece -- and Western Civilization

Language and Learning: Philosophy of Language in the Hellenistic Age

Present Shock in Late Fifth-Century Greece

The Complete Archaeology of Greece: From Hunter-Gatherers to the 20th Century A.D.

Initiation in Ancient Greek Rituals and Narratives: New Critical Perspectives

weapon could not be further increased. Therefore, engineers turned to another source of energy based on twisting thick cords of animal sinews, horse or human hair (women's hair was considered the best) soaked in oil. Such torsion-powered machines were not based around the bow but on an arm inserted into a rope bundle (torsion-spring). The torsion-springs were fastened to a wooden frame and twisted as far as possible by special levers at the top and at the bottom. Such arrow-firing machines with

weapon could not be further increased. Therefore, engineers turned to another source of energy based on twisting thick cords of animal sinews, horse or human hair (women's hair was considered the best) soaked in oil. Such torsion-powered machines were not based around the bow but on an arm inserted into a rope bundle (torsion-spring). The torsion-springs were fastened to a wooden frame and twisted as far as possible by special levers at the top and at the bottom. Such arrow-firing machines with

that was moved from one window to another with the help of a system of pulleys. OPPOSITE TOP The south cross-wall at Miletus is an excellent example of how far the art of fortification had advanced by the end of the period in question. It was built in the late 2nd/1 st century BC, that is, shortly after the city had been annexed by Rome. The wall provides evidence of the most extensive defensive activity ever undertaken in ancient Asia Minor. The only other example of such 'offensive' defence

rulers of strong kingdoms. Autonomous cities, with perhaps the exception of Rhodes, could not afford such fortifications. Medium-sized cities such as Side or Perge built second-rate fortifications with sophisticated multi-level curtains, but with towers only large enough for small-calibre artillery. Poorer cities could only afford third-rate fortifications consisting of plain curtains and small towers sometimes unfit for mounting any artillery. Consequently, many cities could only withstand a

despite the fact that they were built at the same time. One possible explanation for this is the greater significance attached to towers. Lacking the capacity to enfilade the attacking enemy, the latter often became the chief target for assault and had to withstand battering, mining and so on. From the 4th century B C onwards, towers had to become stronger in order to accommodate artillery. Polygonal and Lesbian masonry, though very handsome and providing better cohesion, were the most